For good reason, our Zen tradition is known for being a little serious, perhaps even harsh. The kyosaku is meant to help practitioners stay awake—and it does—but it still looks like someone getting hit with a stick. Linji was known for his deafening shout, and Te Shan for his tendency to beat his students with a staff. Our ancestors often remind us to be single-minded in our pursuit of truth. With death as our constant companion, what room is there for play, for goofing around?

You could easily focus on the dignity, majesty, and life-or-death seriousness of our tradition, if you wanted to. But, you would be forgetting Chin Niu, who would call his monks to lunch by beating a pot, laughing, dancing, and singing, "Bodhisattvas! Come and eat!" You would be forgetting the spontaneous laughter that came about at moments of awakening. You would be ignoring the Pang family's teasing each other as they sharpened their understanding together.

While buddhas and bodhisattvas are traditionally depicted with a slight smile, or at least a rather warm expression, Bodhidharma, the first Zen ancestor in China, sits there scowling. He's a scary sight. His beard is scraggly. He wears his robe over his head, which gives me the impression that he's hiding, that he doesn't want to talk to me. He probably wouldn't want to talk to me, in fact. He brought a teaching "not dependent on words and letters." Hui-Ke had to cut off his own hand just to get into his dokusan room. Bodhidharma was so dead serious and intent on practicing zazen, the legend says, that he sliced off his eyelids to keep from dozing off. (Fortunately for us, his eyelids fell to the ground and a tea plant sprung up, so we can just have some tea to stay alert.) Google image-search "Bodhidharma" and you'll see some serious-looking faces. Our way is difficult, he seems to say, demanding everything. Don't slack off.

This image is different, however. Hanging in the AZC zendo, it shows Bodhidharma playing with a chubby little kitty, and smiling. I've never seen such a depiction of the blue-eyed barbarian. Sure, practice hard, it seems to say, but know that this is all for the sake of liberation. Dogen tells us that if you realize that your mind is unlimited, "your priorities about everything change immediately." Maybe playing with the cat, or tying a pretty red ribbon around his neck, becomes the most important thing. Devote yourself wholeheartedly to this way that directly points to the absolute. Know that your mind is unlimited. Smile. Bodhidharma wants to play.

(Visit Trevor's blog at: http://thebigoldoaktree.blogspot.com/)

When Zen master Fa-ch'an was dying, a squirrel screeched on the roof.

It's "just this" he said, "and nothing more."

Remembering Play

(Kim Mosley)

We sat two periods of zazen today, during which time there were a few kids playing in the yard next to the zendo. At first I was annoyed, because I was having my private conversations with myself, and these kids were interrupting me. Then I started to sense it was me, 55 years ago, playing, not them. I moved from the cushion to the outdoors. I realized I was existing in two "time zones" at the same time. Later, after sitting, I saw the kids through the window. They had red shirts on. No, I thought. I wasn't wearing a red shirt that day!

(more of Kim Mosley's art can be found on his blog: mrkimmosleywrite.blogspot.com)

(more of Kim Mosley's art can be found on his blog: mrkimmosleywrite.blogspot.com)

(daigu)

nine bows

for the bodhisattva

child's play

the thus come one's

true disciple

who teaches children

the games

they know

by heart.

nine bows for bodhichitta,

freeze tag

hide & seek

and the immutable law

of hop scotch

jacks

jump rope

and the fool's favorite

peek-a-boo.

with closed eyes,

I see you.

for the bodhisattva

child's play

the thus come one's

true disciple

who teaches children

the games

they know

by heart.

nine bows for bodhichitta,

freeze tag

hide & seek

and the immutable law

of hop scotch

jacks

jump rope

and the fool's favorite

peek-a-boo.

with closed eyes,

I see you.

play at work, work at play

(Kim Mosley)

Sometimes we mistakenly believe that kids play and adults work, but one just needs to watch a toddler and see how dedicated they are to the task at hand to realize they are learning about their universe in record time and will not (or rarely, as in Jasper's case below) be led astray by any distractions.

Sometimes we mistakenly believe that kids play and adults work, but one just needs to watch a toddler and see how dedicated they are to the task at hand to realize they are learning about their universe in record time and will not (or rarely, as in Jasper's case below) be led astray by any distractions.Adults, on the other hand, with their great understanding of the world, seem to have lots of time for play—sports, movies, and candlelight dinners.

QUESTION: AT WHAT AGE DO HUMANS PLAY? WHY?

(more of Kim Mosley's art can be found on his blog: blog.kimmosley.com)

Daylight Savings

(Cristina Mauro)

Flung across their row of beds

my three boys fell asleep playing.

One lays diagonal across the mattress

chin propped up and arms outstretched.

A small blue airplane in one hand waits

to fly through the line of light beaming

from the flashlight in his other hand.

His twin brother has his head nested on the pillow

and arms down by his sides

but the covers are rumpled

and the headband circled twice around his upper arm

seems to suggest he has unusual powers.

The youngest sleeps upside down

with a red flip flop clinging to one foot.

His stuffed rabbit is not in the usual place

and his hand hangs over the mattress edge

holding a single sheet of blank paper.

The hour that vanished hangs over them and waits.

my three boys fell asleep playing.

One lays diagonal across the mattress

chin propped up and arms outstretched.

A small blue airplane in one hand waits

to fly through the line of light beaming

from the flashlight in his other hand.

His twin brother has his head nested on the pillow

and arms down by his sides

but the covers are rumpled

and the headband circled twice around his upper arm

seems to suggest he has unusual powers.

The youngest sleeps upside down

with a red flip flop clinging to one foot.

His stuffed rabbit is not in the usual place

and his hand hangs over the mattress edge

holding a single sheet of blank paper.

The hour that vanished hangs over them and waits.

2005 Summer Intensive

One hot day during Summer Intensive 2005, four participants (Nancy Webber, Anita Swan, Lila Parrish, Pat Yingst), crazed by the relentless chirping of cicadas and the unceasing watching of their thoughts, unleashed their impulses on the building and grounds of the AZC. Their mayhem did not go un-recorded! See it here.

The Ballad of Bodhidharma

(John Grimes)

Bodhidharma went to China

Just to see what he could see.

When he got there all he said is:

"What will be is what will be.

But delusion mars your vision

Of what is and what has been,

So just sit right down and turn around

And start to practice zen."

"Once you're seated and you're settled

Then you focus on your breath.

In good time it will be obvious

That twixt now and certain death

There's no you, no I, no me, no thee,

He, she, her, it or him.

There's just us, right here, and us, right now.

There is no they or them."

"All appearance is delusion

There is nothing there at all.

But do not activate your mind

When that nothing comes to call.

In the mind, no coughing, sighing

When you hate or when you crave.

There's no gain or loss – don't laugh or cry –

Come join me in my cave!"

Bodhidharma barks and snaps and snarls

And bristles in your face,

Yet he'd love a kiss and cuddle

Any time, most any place.

He's a puzzle, is our Bodhi,

As we struggle to perceive

That the only dharm' of karma is

We get what we receive.

(This can also be sung to the tune of the final rondo of The Elixir of Love by Donizetti)

Just to see what he could see.

When he got there all he said is:

"What will be is what will be.

But delusion mars your vision

Of what is and what has been,

So just sit right down and turn around

And start to practice zen."

"Once you're seated and you're settled

Then you focus on your breath.

In good time it will be obvious

That twixt now and certain death

There's no you, no I, no me, no thee,

He, she, her, it or him.

There's just us, right here, and us, right now.

There is no they or them."

"All appearance is delusion

There is nothing there at all.

But do not activate your mind

When that nothing comes to call.

In the mind, no coughing, sighing

When you hate or when you crave.

There's no gain or loss – don't laugh or cry –

Come join me in my cave!"

Bodhidharma barks and snaps and snarls

And bristles in your face,

Yet he'd love a kiss and cuddle

Any time, most any place.

He's a puzzle, is our Bodhi,

As we struggle to perceive

That the only dharm' of karma is

We get what we receive.

(This can also be sung to the tune of the final rondo of The Elixir of Love by Donizetti)

Showdown at the Genjo Corral

(Peg Syverson)

Austin Zen Center 2003 Summer Intensive

Cast: Dogen, Billy (the kid), Bartender, Wyatt, Shane

Scene: A West Texas saloon, Showdown at the Genjo Corral

The arrival:

[Wyatt, Shane and Billy, seated at the table with a go game between Wyatt and Shane]

[Bartender is wiping off the bar when the robed stranger, Dogen, enters, carrying a set of oryoki bowls and a fan.]

Bartender: What can I do for ye, stranger?

Dogen: Nothing.

Bartender [sets down a shot glass]: Well, what’ll it be?

Dogen: Nothing.

Bartender rolls his eyes and takes away the glass.

Bartender: I guess you’re not from around these parts. So, then, what do you think of West Texas, pardner?

Dogen: As my great granddaddy said, “Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”

The gamblers:

Wyatt: You got that right, stranger. Say, what’s your handle?

Dogen: Dogen

Shane: Why don’t you come along, little dogie, and set right here by me.

[Dogen moves to the table and takes a seat next to Billy]

Wyatt: We’re just having a friendly game of Go with a little wager on the side. Table stakes, nothing much.

Billy [eagerly]: What are you gonna bet, Dogen?

Dogen: Nothing.

The teachings:

On self:

Wyatt: Well, then, what have you got to say for yourself?

Dogen: To study the Buddha way is to study the self;

Billy [helpfully]: Well, if you want to know the way to Buda, it’s a five day ride due east of here.

Wyatt: Hold on, Billy, let the man say his piece. [turns with interest to Dogen]

Dogen:To study the self is to forget the self.

Shane: well, now, Dogie, would that be the ontological self or the psychological self?

[chuckles]

Dogen: To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things.

Wyatt: Hell, talkin’ about myriad things, I got a lot on my plate too. My to-do list is a mile long. But what the Sam Hill are you talking about?

Dogen: When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away.

Billy [excitedly]: You mean, like a lynching?

Dogen: No trace of realization remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly.

Wyatt: What??? Now you’re talking like a crazy man, ain’t he, Shane?

Form and emptiness:

Shane: Wait a minute, Wyatt. I think the man’s actualizing some fundamental point. Lookee here. See that corral? It’s form, and emptiness. Without the fence posts and rails, you got no corral, without the emptiness, you just got you a pile of lumber, and no place to put the herd.

Wyatt (triumphantly) : But supposin’ you was to turn them posts and rails into firewood and burn ‘em up? Then where’s your dadgummed corral, eh?

Dogen: Firewood becomes ash, and it does not become firewood again.

Shane (ruefully): He’s got you there, Wyatt.

The wind

Shane: Wind’s kickin’ up again.

Wyatt [shaking the head]: Like always. And it gets into everything. No point in even fanning yourself.

Dogen: Although you understand that the nature of the wind is permanent, you do not understand the meaning of its reaching everywhere.

Wyatt [annoyed]: Goddamned if I don’t, and I’ve got the sand in my ass to prove it.

Billy: What do you mean, Dogen?

Dogen (fans himself with his fan)

Dogen: It’s possible to illustrate this with more analogies, with birds, and fish, and boats, and so on... but I won’t. The moon is on the dewdrops, farewell, bodhisattvas-mahasattva.

Wyatt [narrowing the eyes]: What did you just call us, son?

Shane: Git along, little Dogie. I’ll enlighten this one.

Exit:

[Shane and Wyatt return to their go game, murmuring and shaking their heads, Billy looks on, and the bartender wipes down the bar.]

Wyatt: Another sake, Bartender!

Dogen, leaving [thoughtfully]: When buddhas are truly buddhas they do not necessarily notice that they are buddhas.

Cast: Dogen, Billy (the kid), Bartender, Wyatt, Shane

Scene: A West Texas saloon, Showdown at the Genjo Corral

The arrival:

[Wyatt, Shane and Billy, seated at the table with a go game between Wyatt and Shane]

[Bartender is wiping off the bar when the robed stranger, Dogen, enters, carrying a set of oryoki bowls and a fan.]

Bartender: What can I do for ye, stranger?

Dogen: Nothing.

Bartender [sets down a shot glass]: Well, what’ll it be?

Dogen: Nothing.

Bartender rolls his eyes and takes away the glass.

Bartender: I guess you’re not from around these parts. So, then, what do you think of West Texas, pardner?

Dogen: As my great granddaddy said, “Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”

The gamblers:

Wyatt: You got that right, stranger. Say, what’s your handle?

Dogen: Dogen

Shane: Why don’t you come along, little dogie, and set right here by me.

[Dogen moves to the table and takes a seat next to Billy]

Wyatt: We’re just having a friendly game of Go with a little wager on the side. Table stakes, nothing much.

Billy [eagerly]: What are you gonna bet, Dogen?

Dogen: Nothing.

The teachings:

On self:

Wyatt: Well, then, what have you got to say for yourself?

Dogen: To study the Buddha way is to study the self;

Billy [helpfully]: Well, if you want to know the way to Buda, it’s a five day ride due east of here.

Wyatt: Hold on, Billy, let the man say his piece. [turns with interest to Dogen]

Dogen:To study the self is to forget the self.

Shane: well, now, Dogie, would that be the ontological self or the psychological self?

[chuckles]

Dogen: To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things.

Wyatt: Hell, talkin’ about myriad things, I got a lot on my plate too. My to-do list is a mile long. But what the Sam Hill are you talking about?

Dogen: When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away.

Billy [excitedly]: You mean, like a lynching?

Dogen: No trace of realization remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly.

Wyatt: What??? Now you’re talking like a crazy man, ain’t he, Shane?

Form and emptiness:

Shane: Wait a minute, Wyatt. I think the man’s actualizing some fundamental point. Lookee here. See that corral? It’s form, and emptiness. Without the fence posts and rails, you got no corral, without the emptiness, you just got you a pile of lumber, and no place to put the herd.

Wyatt (triumphantly) : But supposin’ you was to turn them posts and rails into firewood and burn ‘em up? Then where’s your dadgummed corral, eh?

Dogen: Firewood becomes ash, and it does not become firewood again.

Shane (ruefully): He’s got you there, Wyatt.

The wind

Shane: Wind’s kickin’ up again.

Wyatt [shaking the head]: Like always. And it gets into everything. No point in even fanning yourself.

Dogen: Although you understand that the nature of the wind is permanent, you do not understand the meaning of its reaching everywhere.

Wyatt [annoyed]: Goddamned if I don’t, and I’ve got the sand in my ass to prove it.

Billy: What do you mean, Dogen?

Dogen (fans himself with his fan)

Dogen: It’s possible to illustrate this with more analogies, with birds, and fish, and boats, and so on... but I won’t. The moon is on the dewdrops, farewell, bodhisattvas-mahasattva.

Wyatt [narrowing the eyes]: What did you just call us, son?

Shane: Git along, little Dogie. I’ll enlighten this one.

Exit:

[Shane and Wyatt return to their go game, murmuring and shaking their heads, Billy looks on, and the bartender wipes down the bar.]

Wyatt: Another sake, Bartender!

Dogen, leaving [thoughtfully]: When buddhas are truly buddhas they do not necessarily notice that they are buddhas.

Play Full Out

(Dosho Port)

Dogen Zenji says, To listen to dharma is to cause your consciousness to play freely. This play is not a means but an end in itself. At that time you can have full commitment to play. The power to transform our life is from just playing with wholeheartedness. Naturally, you can play freely within practice. In the process of doing zazen, you can play freely with zazen and produce a new creative life. – Katagiri Roshi

I work in a school for teenagers in a large metropolitan district. Of course, like young people everywhere, they love to play. After a recent break, I asked a student how it was for him. He thought for a long moment and then said, “Well, I’d have to say good.”

“What about it was good?” I asked. After another reflective pause he said in seriousness, “Well, I didn’t get shot this time.”

This young man is not alone. I see many young people whose lives have been shaped by violence, who have gunshot or knife wounds, some of them sport several such urban battle scars with pride. Almost all of them have close relatives in prison.

These young people reflect the larger culture as it appears through popular movies to computer games, a culture increasingly permeated by violence and its glorification. Many of us have become increasingly numb or oblivious to violence, tolerating more and more of the intolerable.

The popularity of violence might be due to how easy and cheap it is to get people’s attention with violence—a lazy way that leaves us yearning for more in the hope that then we might feel alive, like potato chips and their greasy, saltiness that don’t satisfy hunger but leave us wanting more.

What’s this got to do with play?

In my view, the potential of Zen isn’t limited to giving aging boomers something to do in their upper middle years, nor is it about meeting any individual’s need for spiritual trips.

“The wind of Buddhadharma makes manifest the great earth’s gold,” said Dogen. In other words, Zen is about freshly addressing the key issues of our times and encouraging us to assertively make a Buddha out of a mud-ball life.

One of our primary issues, perhaps the challenge for our time, as Thich Nhat Han has long argued, is to make peace fun and interesting. Our survival may depend on it. Soto Zen, I suggest, is a practice of playing full out that offers one challenging way in which we can live a creative and deeply fulfilling life, doing what needs to be done with this precious opportunity of human birth.

Such a Zen has the potential to become a social movement, making playing together with all our hearts in all that we do the society's central organizing principle and our life’s most passionate engagement.

Frequently Dogen emphasizes this point. For example, in “Fukanzazengi” he says, “If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, that in itself is wholeheartedly engaging the Way.”

And above you’ll find Katagiri Roshi’s comment on Dogen’s word, yuge, transforming through play. “This play is not a means but an end in itself. At that time you can have full commitment to play. The power to transform our life is from just playing with wholeheartedness.”

Yuge comprises the root of the name of our little practice place here in White Bear Township, Minnesota Yugeji, or Transforming Through Play Temple. Our most important guideline is to play full out.

By dropping the cowboy tendency to drift into our individual trips and our hungry ghost tendency to wallow in Zen-group-think blather, we are compelled to balance on a tight rope, on a razor’s edge of dynamic aliveness. This is the life vein of vividly hopping along together in this great life.

It certainly beats getting shot.

(Editor's note: Dosho Port is a priest in Katagiri Roshi's lineage who teaches in Minnesota, author of Keep Me in Your Heart a While. Visit his blog: http://wildfoxzen.blogspot.com/)

I work in a school for teenagers in a large metropolitan district. Of course, like young people everywhere, they love to play. After a recent break, I asked a student how it was for him. He thought for a long moment and then said, “Well, I’d have to say good.”

“What about it was good?” I asked. After another reflective pause he said in seriousness, “Well, I didn’t get shot this time.”

This young man is not alone. I see many young people whose lives have been shaped by violence, who have gunshot or knife wounds, some of them sport several such urban battle scars with pride. Almost all of them have close relatives in prison.

These young people reflect the larger culture as it appears through popular movies to computer games, a culture increasingly permeated by violence and its glorification. Many of us have become increasingly numb or oblivious to violence, tolerating more and more of the intolerable.

The popularity of violence might be due to how easy and cheap it is to get people’s attention with violence—a lazy way that leaves us yearning for more in the hope that then we might feel alive, like potato chips and their greasy, saltiness that don’t satisfy hunger but leave us wanting more.

What’s this got to do with play?

In my view, the potential of Zen isn’t limited to giving aging boomers something to do in their upper middle years, nor is it about meeting any individual’s need for spiritual trips.

“The wind of Buddhadharma makes manifest the great earth’s gold,” said Dogen. In other words, Zen is about freshly addressing the key issues of our times and encouraging us to assertively make a Buddha out of a mud-ball life.

One of our primary issues, perhaps the challenge for our time, as Thich Nhat Han has long argued, is to make peace fun and interesting. Our survival may depend on it. Soto Zen, I suggest, is a practice of playing full out that offers one challenging way in which we can live a creative and deeply fulfilling life, doing what needs to be done with this precious opportunity of human birth.

Such a Zen has the potential to become a social movement, making playing together with all our hearts in all that we do the society's central organizing principle and our life’s most passionate engagement.

Frequently Dogen emphasizes this point. For example, in “Fukanzazengi” he says, “If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, that in itself is wholeheartedly engaging the Way.”

And above you’ll find Katagiri Roshi’s comment on Dogen’s word, yuge, transforming through play. “This play is not a means but an end in itself. At that time you can have full commitment to play. The power to transform our life is from just playing with wholeheartedness.”

Yuge comprises the root of the name of our little practice place here in White Bear Township, Minnesota Yugeji, or Transforming Through Play Temple. Our most important guideline is to play full out.

By dropping the cowboy tendency to drift into our individual trips and our hungry ghost tendency to wallow in Zen-group-think blather, we are compelled to balance on a tight rope, on a razor’s edge of dynamic aliveness. This is the life vein of vividly hopping along together in this great life.

It certainly beats getting shot.

(Editor's note: Dosho Port is a priest in Katagiri Roshi's lineage who teaches in Minnesota, author of Keep Me in Your Heart a While. Visit his blog: http://wildfoxzen.blogspot.com/)

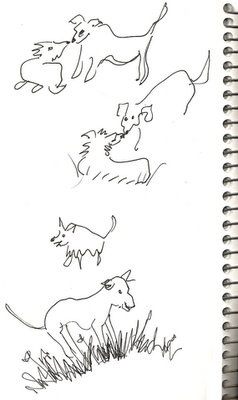

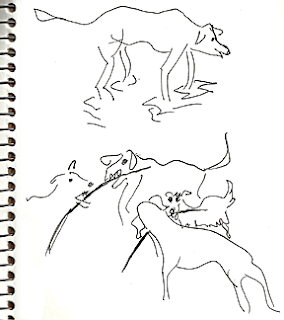

Dog Friends

(Sarah Webb)

My dog Rex, a big hound dog blue heeler mix, just one year old, loves it when I take him to the lake shore in the late afternoon. The lake is down so there are acres for him to run on, and there’s water to splash through and birds to chase. He run almost out of sight, then thunders back and swerves as he gets to me, grinning with loopy joy. That’s a way to be, I think, grinning back. Not the only way but a good way—charging forward, full heartedly, feeling your joy.

Kids can be like that too—full hearted. Sometimes with joy, sometimes screaming their rage or sorrow. They run and stumble and leap right back up so they can keep on playing.

That’s another way Rex is like a kid. He loves to play. About a month ago he met another dog along the shore, a furry-coated little beast about half Rex’s size. He reminds me of Missy, my last dog, who died last summer, but this dog is bigger and much healthier.

After a few minutes of bristling, he realized Rex wanted to play, and they started to chase each other. We meet him almost every day now, and the two of them chase and tumble and nip and wrestle.

Kids will find the possibilities in a situation. A table? They’ll sit at it, sit on it, crawl under it, tip it on its side, slide things down it, put a blanket over it, lie underneath it and look up.

That’s what these dogs do too. Each day they find a new game. One will hide down in a hollow and burst out to surprise the other. They’ll chew down sticks from the dried brush and tug-a-war with them. They’ll steal the sticks from each other and race through the open with the other one in chase.

They leap into the ponds and splash about. They take a stick and trot together.

Yesterday we went further down the shore into heavy brush and they barreled through the brush in circles, apparently just for the joy of crashing about and following the leader. When they’re exhausted—and it takes a lot to exhaust them—they’ll lie on each other in a heap and pant. Then Rex will leap up and off they go again.

There’s something about playing. Children play and dogs too, but so do many other creatures. Ravens do daredevil acrobats. Bear cubs wrestle and tumble. Lambs leap and run. Watching the dogs I see that it’s more than delight in motion. There’s a make-believe to it, as there is in children’s play. I’ll pretend to be angry and chase you and steal from you, but we know it’s not for real. We act like we’re separate and hostile, but we know we’re not at all. Instead we are making something together, a game.

Are we one or are we two? the dogs ask, and their game says, one. One, and a one that is bursting out into creation, making not just this world but pretend worlds and painting worlds and hitting balls and catching them worlds, and for dogs, chasing and splashing and tumbling worlds. A one that has inherent in it, play.

Rex running on the shore

Kids can be like that too—full hearted. Sometimes with joy, sometimes screaming their rage or sorrow. They run and stumble and leap right back up so they can keep on playing.

That’s another way Rex is like a kid. He loves to play. About a month ago he met another dog along the shore, a furry-coated little beast about half Rex’s size. He reminds me of Missy, my last dog, who died last summer, but this dog is bigger and much healthier.

After a few minutes of bristling, he realized Rex wanted to play, and they started to chase each other. We meet him almost every day now, and the two of them chase and tumble and nip and wrestle.

Kids will find the possibilities in a situation. A table? They’ll sit at it, sit on it, crawl under it, tip it on its side, slide things down it, put a blanket over it, lie underneath it and look up.

That’s what these dogs do too. Each day they find a new game. One will hide down in a hollow and burst out to surprise the other. They’ll chew down sticks from the dried brush and tug-a-war with them. They’ll steal the sticks from each other and race through the open with the other one in chase.

They leap into the ponds and splash about. They take a stick and trot together.

Yesterday we went further down the shore into heavy brush and they barreled through the brush in circles, apparently just for the joy of crashing about and following the leader. When they’re exhausted—and it takes a lot to exhaust them—they’ll lie on each other in a heap and pant. Then Rex will leap up and off they go again.

There’s something about playing. Children play and dogs too, but so do many other creatures. Ravens do daredevil acrobats. Bear cubs wrestle and tumble. Lambs leap and run. Watching the dogs I see that it’s more than delight in motion. There’s a make-believe to it, as there is in children’s play. I’ll pretend to be angry and chase you and steal from you, but we know it’s not for real. We act like we’re separate and hostile, but we know we’re not at all. Instead we are making something together, a game.

Are we one or are we two? the dogs ask, and their game says, one. One, and a one that is bursting out into creation, making not just this world but pretend worlds and painting worlds and hitting balls and catching them worlds, and for dogs, chasing and splashing and tumbling worlds. A one that has inherent in it, play.

Playing in Prison

(Lila Parrish)

Play shows up with surprising gifts sometimes. I volunteer at the state prison in Lockhart as part of Inside Meditation, the prison program that AZC is part of. The class I teach is on meditation and occasionally I share some circle dance as part of that. When the women come into the classroom and sit down they are carrying the energy of living in large “pods” or units and sharing a cell with another woman. There is no privacy and even smiling at someone can get them in trouble at times. As a result of that environment many of them have guarded faces. The circle dances are lively and the novelty of dancing brings down that guardedness. Their faces light up with laughter and the delight of moving safely and playfully together. When a dance ends I invite them to look around the circle and notice the difference in how their faces look. Next I ask them to share anything they would like. “I forgot I was in prison while I was dancing.” “I felt like a child playing.” Our dancing together can give some moments of freedom and of remembering a younger, happier self. Gifts of freedom and youthful energy for at least two women. And for me the gift of deep gratitude for their willingness to dance and play with me.

March 2010

March 2010

Play

(Sarah Weintraub)

It is not sunny. Pieces of a to-do list keep bursting into my head and making me stand there thinking, instead of moving into the next yoga pose. I could’ve gotten up earlier today, really. And then gotten out of bed sooner, actually. We are out of milk, and everything, because my roommate didn’t go grocery shopping. And she is the easiest person in the world to live with, by the way—how will I ever live with a partner? Here I am, again, on a thought, and forgetting which pose is next. And why don’t more people know about the boycott against Coca-Cola for killing trade unionists in Colombia? And I really do need to sweep the house before the meeting here tonight.

And then there is the sitting still for a while, with a rakusu, cross-legged. Then I put a few dollars in my pocket and pull on my red suede Medellin boots and walk a block to the 24 Liquor Grocery, which is not actually open twenty-four hours a day, but is open on Monday at seven AM, which it is. On the walk, I am surprised by the pleasure of breathing, of breath entering and leaving, and by the pleasure of walking, of my muscles moving. It is not so cold out, and the birds go on and on and on, like it’s springtime, which maybe it is.

We are not going to fail at our lives, you know.

I will lead a very interesting life. I will be very alive. I will enjoy it very much. I will keep doing my best—but my best to be kind, to all beings, starting with this one right here.

I will remember this; and I will forget it again. And I will remember and forget and remember and forget. Just like we return to our breath in zazen, I will return to this being at home in myself, to being relaxed and joyful, and to curiously relishing the unfolding of this life.

(Sarah Weintraub is the Executive Director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.)

And then there is the sitting still for a while, with a rakusu, cross-legged. Then I put a few dollars in my pocket and pull on my red suede Medellin boots and walk a block to the 24 Liquor Grocery, which is not actually open twenty-four hours a day, but is open on Monday at seven AM, which it is. On the walk, I am surprised by the pleasure of breathing, of breath entering and leaving, and by the pleasure of walking, of my muscles moving. It is not so cold out, and the birds go on and on and on, like it’s springtime, which maybe it is.

We are not going to fail at our lives, you know.

I will lead a very interesting life. I will be very alive. I will enjoy it very much. I will keep doing my best—but my best to be kind, to all beings, starting with this one right here.

I will remember this; and I will forget it again. And I will remember and forget and remember and forget. Just like we return to our breath in zazen, I will return to this being at home in myself, to being relaxed and joyful, and to curiously relishing the unfolding of this life.

(Sarah Weintraub is the Executive Director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)